It was a

Saturday afternoon. I was sitting with my friend Afia, in a local restaurant, chatting

and laughing. Brian Adam’s “Summer of 69” playing in the background made the

entire café come to life. This was a rare treat for us, as Afia was a doctor

always busy with patients and off duty calls and I was always working to a

journalist’s schedule.

Another

issue for us was that our husbands were lazy creatures. After work their

favourite pass time was to watch sports TV and do nothing, so the entire load

of domestic and social responsibilities also fell onto our laps.

But

always, it was a pleasure to see each other.

She was

filling me in on her son’s latest girlfriend when her cell phone rang. She held

up a finger and took the call, still smiling, but only for a moment. Her

expression collapsed, her face became white, and tears filled her eyes. She

nodded briefly and switched off her cell. She looked towards me while a single tear

roll down her cheek and said that Tania had been shot. By her husband.

“What?” I nearly

screamed and put the tea cup with my shaking hand on the table.

Tania was

the biological mother of my adopted daughter Sana who was then a chatty

five-year-old.

“Why. What

was the reason?” I asked Afia.

“You know

as well as I,” she said. “He must have found out. But I’ll get you the details

as soon as I know”.

I quickly left the restaurant because I wanted

to be with Sana.

I remember

it being a beautiful spring morning when I’d received a call from my friend

Afia. She had arranged a meeting between Tania, Sana’s mother, who wanted to

abort her unborn baby, and myself. Tania was 24 weeks into the pregnancy and

doctors were refusing to abort, as there was a risk involved. Afia knew of my

intention to adopt a child, so she’d asked me to come in.

Next day when

I arrived at Afia’s clinic to meet Tania, I was struck by her beauty and

decency. She was a gorgeous young girl of about eighteen who was sitting with

her very charming and elegant mother. She wrapped herself in a traditional

shawl. They were Afghans but based in Peshawar. My first impression was that

they belong to an educated and affluent class.

“She was engaged to her cousin,” her mother

told me, while Tania looked at her lap.

“They were

to get married last month but he died in an accident six weeks before the

wedding,” she told me without controlling her tears. “We are tribal people. Her

brothers can’t know about her pregnancy – they’ll kill her in the name of honour,

and I don’t want my son behind bars and my daughter in a grave in my back

garden. We are people who respect values.… I don’t know how she got into this

mess”.

I looked

at Tania for an elaboration of the word “mess” but none was forthcoming. For

Tania it was perhaps love, I thought, but she did not utter a word, and her

only expression were the tears which rolled down her pink cheeks. I wondered

whether she was crying because of the death of her fiancé or for giving away

the only living token of their love.

As we signed

the documents for adoption in front of Afia, who was handling this on the

hospital’s behalf, Tania looked at me and spoke for the first time. “Will I

ever be able to see her?” she asked.

Before I

could answer, Afia interrupted in a stern voice: “No.”

Tania

tried to control herself, but she couldn’t. Her hands shook as she signed the

papers and put the pen back on the table. Then she put her head on her mother’s

shoulder and cried like a baby.

I knew

that the heaven and earth felt her pain.

After few

months when I was called to pick Sana from the hospital, I’d met Tania and her

mother again and this time Tania looked even more disturbed than before.

Although she was wearing a beautiful pink and blue dress, her shoulder length

hair were neatly tied I could sense her distress as she put her baby in my lap.

Usually it

is not the mother who handed over the baby; it is the hospital staff, but Tania

had insisted she wanted to do the task herself. “Please call her Sana,” she

said, her voice hoarse. “It’s her father’s name.”

I agreed,

and as she left the room she’d turned back and glanced at Sana for the last

time.

Although

that happened five years ago it only seems yesterday. In the meanwhile, I’d

heard that Tania had finally gotten married. Of course I assumed she hadn’t

told her new husband about her child. How could she, in a society where an

unmarried pregnancy is a death sentence? But despite her secrecy, despite her

complete separation from her child, her “crime” had somehow been discovered,

and the sentence carried out.

As soon as

I got home, I pulled Sana into a hug. She saw tears in my eyes and asked, “Mama,

Mama, why are you crying? Is somebody dead?”

“Yes,” I

said, “My friend died”

“How did

she die?” Sana asked.

I had to ignore

her question, how could I explain?

“Don’t cry,

Mummy. She is in a good place. Didn’t you say dead people go to heaven?”

“Yes,” I

said loudly. “She is in a much better place.” I hugged Sana again and wondered,

Will I ever have the strength to explain her mother’s death?

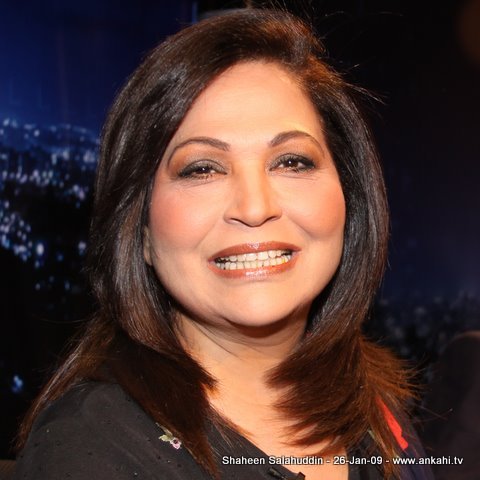

Shaheen Salahuddin has been a Senior Anchor/Journalist for the last 20 years. She headed the first

private news channel in Pakistan and has over three thousand TV talk shows to

her credit. Originally from Karachi, Pakistan, she now lives in Toronto,

Canada.

See Brian Henry’s schedule here, including writing workshops and creative writing courses

in Algonquin Park, Bolton, Barrie, Brampton, Burlington,

Caledon, Georgetown, Guelph, Hamilton, Kingston, Kitchener, London, Midland,

Mississauga, Newmarket, Oakville, Ottawa, Peterborough, St. Catharines, St.

John, NB, Sudbury, Thessalon, Toronto, Windsor, Woodstock, Halton,

Kitchener-Waterloo, Muskoka, Peel, Simcoe, York Region, the GTA, Ontario and

beyond.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.