To be Welsh on Sunday

To be Welsh on Sunday in a dry area of Wales

is to wish, for the only time in your life,

that you were English and civilized,

and that you had a car or a bike and could drive or pedal

to your heart's desire, the county next door, wet on Sundays,

where the pubs never shut and the bar is

a paradise

of elbows in your ribs and the dark liquids flow,

not warm, not cold, just right, and family and friends

are there beside you shoulder to

shoulder,

with the old ones sitting indoors by the

fire in winter

or outdoors in summer, at a picnic table

under the trees

or beneath an umbrella that says Seven Up and Pepsi

(though nobody drinks them) and the umbrella is a sunshade

on an evening like this when the sun is still high

and the children tumble on the grass playing

soccer and cricket and it's "Watch your beer, Da!"

as the gymnasts vault over the family dog till it hides

beneath the table and snores and twitches until

"Time, Gentlemen, please!" and

the nightmare is upon us

as the old school bell, ship's bell, rings out its brass warning

and people leave the Travellers' Rest, the Ffynnon Wen,

The Woodville, The Antelope, The Butcher's, The White Rose,

The Con Club, the Plough and Harrow, The Flora, The Pant Mawr,

The Cow and Snuffers – God bless them all, I knew them in my prime.

Sheep

Wales is whales (with an aitch)

to my daughter

who has only been there once on holiday,

very young, to see her grandparents,

a grim old man and a wrinkled woman.

They wrapped her in a shawl and hugged her until

she cried herself to sleep suffocating

in a straitjacket of warm Welsh wool.

So how do I explain the sheep? They are

everywhere, I say, on lawns and in gardens.

I once knew a man whose prize tulips

were eaten by a sheep, a single sheep

who sneaked into the garden on market day

when he left the gate ajar. They get everywhere,

I say, everywhere. Why, I remember riding

in

a passenger train and seeing five sheep travelling

on a coal truck leering, like tourists travelling

God knows where and bleating fiercely

as they went by.

In Wales, I say, sheep are magic.

When you travel to London on the train,

just before you leave Wales at Severn Tunnel Junction,

you must lean out of the carriage window and say

"Good morning, Mister Sheep!" And if he looks up,

your every wish will be granted.

And look at that poster on the wall: a hillside

of white on green, and every sheep as still as a stone,

and each white stone a roche moutonnée.

Swansea

To be Welsh in Swansea is to know

each stop on the Mumbles Railway:

Singleton, Blackpill, the Mayals, West Cross,

Oystermouth, the Mumbles Pier.

It's to remember that the single lines turn double

by Green's ice-cream stall, down by the Recreation Ground,

where the trams fall silent, like dinosaurs, and wait,

without grunting, for one to pass the other.

It's to read the family names on the War Memorial on the

Prom.

It's to visit Frank Brangwyn in the Patti Pavilion

and the Brangwyn Hall. It's to talk to the old men

playing bowls in Victoria Park.

It's to know that starfish stretch

like a mysterious constellation, at low tide,

when the fishnets glow with gold and silver,

and the banana boats bob in the bay,

waiting to enter harbor, and the young boys dive from

the sewer pipes without worrying about pollution.

But when the tide turns, the Mumbles Railway has been sold

to a Texan, the brown and yellow busses no longer run

to Pyle Corner, Bishopston, Pennard, Rhossili, sweet names

of tide and time, where I see my father fishing still

for salmon bass, casting his lines at the waves

as they walk wet footprints up the beach

to break down the sand-castle walls I built

to last forever on the Swansea sands.

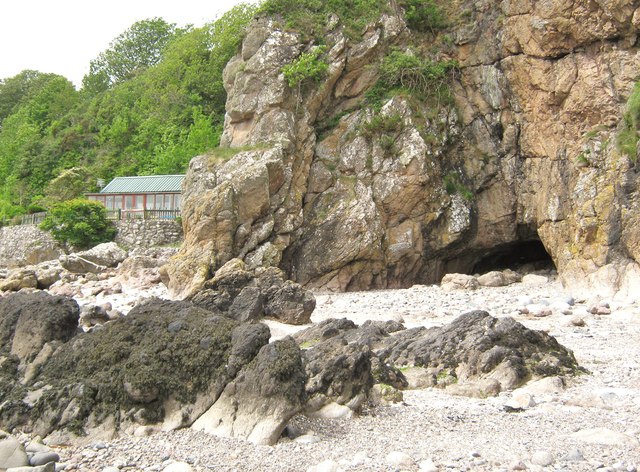

In

the cave

(Brandy Cove, Gower)

No: I do not understand these things.

I have had few visions.

No bush has actually burned for me.

Though I have sat in this cave for many a day

I have heard no thunder, no earthquake,

and no thin, small voice has called my name.

I have only heard the wind and the waves

and the sigh of the seabirds endlessly flying.

Who set the curlew's cry between my lips?

Who dashed the salt taste from my tongue?

I will never forget the wet sand foaming

between my toes nor the cracked rock

crumbling under my hand... yet I never fell,

nor was I trapped by the sea below.

Roger Moore is an award-winning poet and short-story writer. Born in the same town as Dylan Thomas, he emigrated from Wales to Canada in 1966. An award-winning author, CBC short story finalist (1987 and 2010), WFNB Bailey award (poetry, 1989 & 1993), WFNB Richards award (prose, 2020), he has published 5 books of prose and 25 books and chapbooks of poetry.

These four pieces are all from his latest book: On Being Welsh in a land ruled by the English. Read more here. Available

from Amazon here.

Over 150 of his poems and short stories have appeared in 30 Canadian magazines and literary reviews, including Arc, Ariel, The Antigonish Review, the Fiddlehead, the Nashwaak Review, Poetry Toronto, Poetry Canada Review, the Pottersfield Portfolio and The Wild East. He and his beloved, Clare, live in Island View, New Brunswick, with their cat, Princess Squiffy, but they live on the far side of the hill from the St. John River, with the result that there is not an island in view from their windows in Island View. Visit Roger’s website here.

See Brian Henry’s schedule here, including online and in-person writing workshops, weekly

writing classes, and weekend retreats in Algonquin Park, Alliston, Bolton,

Barrie, Brampton, Burlington, Caledon, Collingwood, Georgetown, Georgina,

Guelph, Hamilton, Jackson’s Point, Kingston, Kitchener-Waterloo, London,

Midland, Mississauga, Oakville, Ottawa, Peterborough, St. Catharines,

Southampton, Sudbury, Toronto, Windsor, Woodstock, Halton, Muskoka, Peel,

Simcoe, York Region, the GTA, Ontario and beyond.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.